History and Culture

History of Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia was constantly fought over by the British and the French during the 18th century.

According to some, Saint Lucia was first inhabited sometime between 1000 and 500 BC by the Ciboney people, but there is little evidence of their presence on the island. The first proven inhabitants were the peaceful Arawaks, believed to have come from northern South America around 200-400 AD, as there are numerous archaeological sites on the island where specimens of the Arawaks’ well-developed pottery have been found. There is evidence to suggest that these first inhabitants called the island Iouanalao, which meant ‘Land of the Iguanas’, due to the island’s high number of iguanas.

When the island was first discovered by Europeans is disputed. Some claim that Christopher Columbus sighted the island during his second voyage in 1493, while others claim that Juan de la Cosa noted it on his maps in 1499, and that the island is included on a globe in the Vatican made in 1502.

However, it is doubtful that Columbus passed St Lucia during his second voyage, as the island lies far south of his known route on that voyage; Juan de la Cosa was exploring northern South America in 1499 and it’s obvious that the claim about him naming St Lucia El Falcon refers to the state Falcón in northern Venezuela; and there is no known globe in the Vatican Library from the early 1500s.The more aggressive Caribs arrived around 800 AD, and seized control from the Arawaks by killing their men and assimilating the women into their own society. They called the island Hewanarau, and later Hewanorra. This is the origin of the name of the Hewanorra International Airport in Vieux Fort. The Caribs had a complex society, with hereditary kings and shamans. Their war canoes could hold more than 100 men and were fast enough to catch a sailing ship. They were later feared by the invading Europeans for their ferocity in battle.

In the late 1550s the French pirate François le Clerc (known as Jambe de Bois, due to his wooden leg) set up a camp on Pigeon Island, from where he attacked passing Spanish ships.

Around 1600, the first European camp was started by the Dutch, at what is now Vieux Fort. In 1605, an English vessel called the Olive Branch was blown off-course on its way to Guyana, and the 67 colonists started a settlement on Saint Lucia. After five weeks, only 19 survived, due to disease and conflict with the Caribs, so they fled the island.

In 1635, the French officially claimed the island but didn’t settle it. Instead, it was the English who attempted the next European settlement in 1639, but that too was wiped out by the Caribs. In 1643, a French expedition sent out from Martinique by Jacques Dyel du Parquet, the governor of Martinique, established a permanent settlement on the island. De Rousselan was appointed the island’s governor, took a Carib wife and remained in post until his death in 1654.

In 1664, Thomas Warner (son of the governor of St Kitts) claimed Saint Lucia for England. He brought 1,000 men to defend it from the French, but after two years, only 89 survived, mostly due to disease. In 1666 the French West India Company resumed control of the island, which in 1674 was made an official French crown colony as a dependency of Martinique.

Both the British, with their headquarters in Barbados, and the French, centered on Martinique, found Saint Lucia attractive after the sugar industry developed, and during the 18th century the island changed ownership or was declared neutral territory a dozen times, although the French settlements remained and the island was a de facto a French colony well into the 18th century.

In 1722, the George I of Great Britain granted both Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent to John Montagu, 2nd Duke of Montagu. He in turn appointed Nathaniel Uring, a merchant sea captain and adventurer, as deputy-governor. Uring went to the islands with a group of seven ships, and established settlement at Petit Carenage. Unable to get enough support from British warships, he and the new colonists were quickly run off by the French.

During the Seven Years’ War Britain occupied Saint Lucia for a couple of years, but gave the island back at the Treaty of Paris on 10 February 1763. Like the English and Dutch on other islands, the French began to develop the land for the cultivation of sugar cane as a commodity crop on large plantations in 1765. Colonists who came over were mostly indentured white servants serving a small percentage of wealthy merchants or nobles.

Near the end of the century, the French Revolution occurred. A revolutionary tribunal was sent to Saint Lucia, headed by captain La Crosse. Prior to this, the slaves had heard about the revolution and walked off their jobs in 1790-1 to work for themselves. Bringing the ideas of the revolution to Saint Lucia, La Crosse set up a guillotine used to execute Royalists. In 1794, the French governor of the island declared that all slaves were free, as also happened on Saint-Domingue.

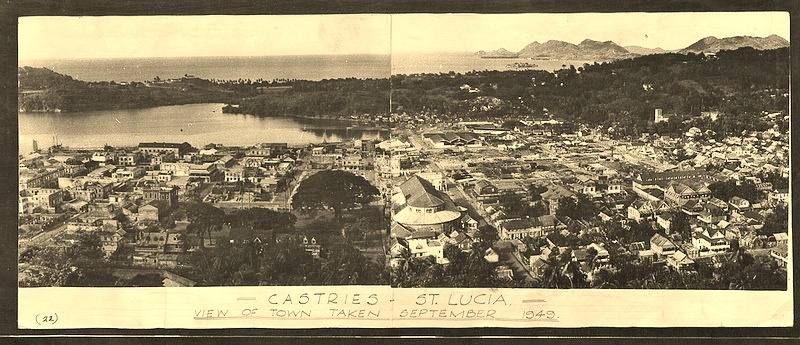

A short time later, the British invaded in response to the concerns of the wealthy plantation owners, who wanted to keep sugar production going. On 21 February 1795, a group of rebels, led by Victor Hugues, defeated a battalion of British troops. For the next four months, a group of recently freed slaves known as the Brigands forced out not only the British army, but every white slave-owner from the island (coloured slave owners were left alone, as in Haiti). In 1796 Castries was burned as part of the conflict.

In 1803, the British finally regained control of the island and restored slavery. Many of the rebels escaped into the thick rain forests, where they evaded capture and established maroon communities.[4] The same year, the French withdrew their forces from Saint-Domingue after losing two-thirds of the 20,000 soldiers they had sent there against the slave revolt. The new leaders of Haiti declared its independence in 1804, the first black republic in the Caribbean, and the second republic in the Western Hemisphere.

The British abolished the African slave trade in 1807; they acquired Saint Lucia permanently in 1814. It was not until 1834 that they abolished the institution of slavery. Even after abolition, all former slaves had to serve a four-year “apprenticeship,” during which they had to work for free for their former masters for at least three-quarters of the work week. They achieved full freedom in 1838. By that time, people of African ethnicity greatly outnumbered those of ethnic European background. Some people of Carib descent also comprised a minority on the island.

Also in 1838, Saint Lucia was incorporated into the British Windward Islands administration, headquartered in Barbados. This lasted until 1885, when the capital was moved to Grenada.

Increasing self-government has marked St Lucia’s 20th-century history. A 1924 constitution gave the island its first form of representative government, with a minority of elected members in the previously all-nominated legislative council. Universal adult suffrage was introduced in 1951, and elected members became a majority of the council. Ministerial government was introduced in 1956, and in 1958 St. Lucia joined the short-lived West Indies Federation, a semi-autonomous dependency of the United Kingdom. When the federation collapsed in 1962, following Jamaica’s withdrawal, a smaller federation was briefly attempted. After the second failure, the United Kingdom and the six windward and leeward islands—Grenada, St. Vincent, Dominica, Antigua, St. Kitts and Nevis and Anguilla, and St. Lucia—developed a novel form of cooperation called associated statehood.

As an associated state of the United Kingdom from 1967 to 1979, St. Lucia had full responsibility for internal self-government but left its external affairs and defense responsibilities to the United Kingdom. This interim arrangement ended on February 22, 1979, when St. Lucia achieved full independence. St. Lucia continues to recognize Queen Elizabeth II as titular head of state and is an active member of the Commonwealth of Nations. The island continues to cooperate with its neighbors through the Caribbean community and common market (CARICOM), the East Caribbean Common Market (ECCM), and the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS).

The Flag of Saint Lucia

The national flag of Saint Lucia was adopted on March 1, 1967, upon achieving self government. The flag was designed by Dunstan St. Omer.NATIONAL-FLAG\

On a plain blue field, a device consisting of a white and black triangular shape, at the base of which a golden triangle occupies a central position. The triangles are superimposed on one another the black on the white, and the gold on the black. The black ends as a three-pointed star in the centre of the flag. The width of the white part of the triangle is one-and-a-half inches on both sides of the black. The distance between the peaks of the black and white triangles is four inches. The triangles share a common base the length of which is one-third of the full length of the flag.

The blue colour represent fidelity. It reflects the tropical sky and also the emerald surrounding waters of the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The gold represents the prevailing sunshine in the Caribbean and prosperity. The triangles represent the mountains in St. Lucia. The Triangle, the shape of which is the partition isosceles triangle, is reminiscent of the island’s famous twin Pitons at Soufriere, rising sheer out of the sea, towards the sky -themselves, a symbol of the hope and aspirations of the people.

Coat of Arms of Saint Lucia

The coat of arms of Saint Lucia was designed by Sydney Bagshaw in 1967. The coat of arms is made of a blue shield with a stool, two roses and two fleur de lis. The shield is supported by two Saint Lucian parrots. Beneath the shield is the national motto, where as above the shield there is a torch and on ornament. The symbolism of the elements are:

- Tudor Rose – England

- Fleur de lis – France

- Stool – Africa

- Torch – Beacon to light the path

- Saint Lucia Parrot – Amazona Versicolor, the national bird

- Motto: “The land, the people, the light”

National Anthem of Saint Lucia

“Sons and Daughters of Saint Lucia” is the national anthem of Saint Lucia, first adopted in 1967 upon achieving self-government, and confirmed as the official anthem upon independence in 1979.

The lyrics were written by Charles Jesse, and the music by Leton Felix Thomas.

Lyrics:

Sons and daughters of Saint Lucia,

love the land that gave us birth,

land of beaches, hills and valleys,

fairest isle of all the earth.

Wheresoever you may roam,

love, oh, love our island home.

Gone the times when nations battled

for this ‘Helen of the West’,

gone the days when strife and discord

Dimmed her children’s toil and rest.

Dawns at last a brighter day,

stretches out a glad new way.

May the good Lord bless our island,

guard her sons from woe and harm,

may our people live united,

strong in soul and strong in arm!

Justice, Truth and Charity,

our ideal for ever be!

National Dress of Saint Lucia

The Madras, also called the Jip or Jupe, is the national dress of the country of Saint Lucia. A traditional five piece costume it was originally derived from the Wob Dwyiet (or Wobe Dwiette), a grand robe worn by the earlier French settlers, and this garment is also recognised as a national dress of the country. The Madras is the traditional dress of the women and girls of St. Lucia, and its name is derived from the Madras cloth, a fabric used in the costume.

The origins of the Madras lie in the pre-emancipation days of St. Lucia, when African slaves on the island would don the colourful dress during feast days. Beginning in the late 17th century, slaves on the island were forced to wear the livre of the estate to which they belonged. Normally a single colour, one piece item, originally worn as a sarong, later becoming a simple tunic with holes for the arms and head, and a simple rope belt.

During Sundays and holidays, the slaves could normally wear what they wished, and through monies earned through selling produce from small plots of land, they would often buy colourful cloth. On feast days and special occasions, free women and slaves would wear the colourful clothes, now known as Creole dress.

Towards the end of the 18th century the Indian cotton known as ‘muchoir madras’ became popular amongst the Creole women, and eventually replaced the white cotton head kerchief. The material was soon used for scarfs and then the ‘jupe’ or skirt. With the fashion for ribbons becoming popular, women added them to the lace on the arms and the neck of their chemise. The chemise, once fashionably long, became shorter until replaced by a blouse and petticoat, but still with the threaded ribbons.

The Madras today is almost identical to the traditional costumes worn by other former French colonies of the Caribbean, including the neighbouring islands of Martinique, Guadeloupe and Dominica. In 2004 a national awareness campaign was launched by the St. Lucian government during the 25th anniversary of the country’s Independence. Both the Madras and the Wob Dwyiet, recognized as symbols of the country, were included in this campaign.

The Madras is made up of five individual pieces of clothing. The costume comprises a white cotton or poplin blouse, known in French Creole as a chimiz decolté or chemise decoltee, finished with Broderie Anglaise and red ribbons. The second item is an ankle length skirt, again trimmed with lace and red ribbons; which has two gathers towards the lower end of the garment. The third item is the shorter outer skirt, made of Madras material, to which the costume is named. The Madras material is used again in the fourth item, the head piece, known as the Tête en l’air or tèt anlè; a square or rectangular piece of cloth worn over the forehead and folded to display varying numbers of peaks. The head scarf can be tied in a ceremonial fashion or can be worn to show the availability of the woman in courtship, depending on the number of peaks tied into it. One peak represents that the woman is single, two that she is married, three that she is widowed or divorced, and four that she is available to any who tries. The final item is a triangular silk scarf, foulard, pinned to the left shoulder, its apex at the end of the elbow and tucked into the waist of the skirt.

The costume is traditionally worn on Independence Day, National Day and Creole Day (Jounen Kwéyòl). It is also worn when dancing the Quadrille, which has been adopted by the country as the national dance.

National Bird

The Saint Lucia Amazon (also known as the Saint Lucia Parrot) (Amazona versicolor) is a species of parrot in the Psittacidae family. It is endemic to Saint Lucia and is the country’s national bird.NATIONAL-BIRD

It was first described by Miller in 1776, this beautiful parrot is, and always has been found only in Saint Lucia. It is predominantly green in colour, and a typical specimen has a cobalt blue forehead merging through turquoise to green on the cheeks and a scarlet breast.

There are no visible differences between the two sexes. Mating for life and maturing after five years, these long-lived birds are cavity nesters, laying two to three white eggs in the hollow of a large tree during the onset of the dry season between February and April. Incubation commences on the appearance of the second egg and lasts 27 days. The young fledge leave the nest 67 days after hatching.

Today the parrot, and most other forms of wildlife are absolutely protected in the country, because Saint Lucia’s National Bird remains an endangered species.

National Flower, PLant and Tree

The Rose and the Marguerite are the symbols of the two flower societies of Saint Lucia. The national tree of Saint Lucia is Calabash, where as the national plant is Bamboo.

Rose

is a woody perennial of the genus Rosa, within the family Rosaceae. There are over 100 species. They form a group of plants that can be erect shrubs, climbing or trailing with stems that are often armed with sharp prickles. Flowers vary in size and shape and are usually large and showy, in colours ranging from white through yellows and reds. Most species are native to Asia, with smaller numbers native to Europe, North America, and northwest Africa. Species, cultivars and hybrids are all widely grown for their beauty and often are fragrant. Rose plants range in size from compact, miniature roses, to climbers that can reach 7 meters in height. Different species hybridize easily, and this has been used in the development of the wide range of garden roses. The name rose comes from French, itself from Latin rosa.

Marguerite – Argyranthemum (marguerite, marguerite daisy, dill daisy) is a MARGUERITE-FLOWERgenus of flowering plants belonging to the family Asteraceae. Members of this genus are sometimes also placed in the genus Chrysanthemum. The genus is endemic to Macaronesia, occurring only on the Canary Islands, the Savage Islands, and Madeira.

Calabash Tree – Crescentia (calabash tree, huingo, krabasi, or kalebas) is a genus of six species[1] of flowering plants in the family Bignoniaceae, native to southern North America, the Caribbean, CentralCALABASH-TREE America and northern South America. The species are small trees growing to 10 m (35 ft) tall, and producing large spherical fruits, with a thin, hard shell and soft pulp,[2] up to 25 cm (10 in) in diameter.

Bamboo Tree - Bamboo Listeni/bæmˈbuː/ (Bambuseae) is a tribe of flowering perennial evergreen plants in the grass family Poaceae, subfamily Bambusoideae, tribe Bambuseae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. In bamboos, the internodal regions of the stem are hollow and the vascular bundles in the cross section are scattered throughout the stem instead of in a cylindrical arrangement. The dicotyledonous woody xylem is also absent. The absence of secondary growth wood causes the stems of monocots, even of palms and large bamboos, to be columnar rather than tapering. Bamboos are some of the fastest-growing plants in the world, due to a unique rhizome-dependent system. Bamboos are of notable economic and cultural significance in South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia, being used for building materials, as a food source, and as a versatile raw product.

Credits: wikipedia.org, the free encyclopedia

Contact Us:

Address:

630 3rd Avenue

7th Floor

New York, NY, 10017

Phone: (212) 697-9360

Fax:

(212) 697-4993

Email: sluconsulateny@govt.lc

Consulate General of Saint Lucia in New York